From ‘Aha!’ to ‘Haha!’: Humor as a Case Study in the Parsimony of Predictive Processing

Abstract: What constitutes a powerful theory in the cognitive sciences? Amid a fragmented landscape of domain-specific explanations, the theoretical virtues of parsimony (explaining much with little) and breadth of explanatory scope have become paramount. This paper argues that the Predictive Processing Framework (PPF), which models the brain as a hierarchical prediction-error minimization engine, exhibits these virtues to a compelling degree. We will use the notoriously difficult and multifaceted phenomenon of humor as a decisive case study. We argue that PPF’s single, core mechanism can furnish an elegant and continuous explanation for a wide spectrum of humor, from the simple resolution of a pun to the persistent, unresolvable absurdity of nonsense. By demonstrating its ability to account for this seemingly frivolous, yet cognitively complex, human experience, we reveal PPF’s profound utility as a potentially unifying theory of mind.

Keywords: Predictive Processing, Humor, Philosophy of Science, Parsimony, Cognitive Science, Prediction Error, Nonsense, Computational Neuroscience.

1. Introduction: The Search for a Unified Theory of Mind

In the marketplace of ideas, theories are judged not only by their accuracy but also by their elegance and power. Philosophers of science articulate this intuition through the language of theoretical virtues, chief among them parsimony and explanatory scope. A parsimonious theory wields a single, powerful mechanism rather than a collection of ad-hoc rules, while a theory with broad explanatory scope can account for a wide and varied range of phenomena. For decades, the cognitive sciences have resembled a fragmented toolkit, with bespoke theories for perception, motor control, learning, and language. The promise of a truly grand unifying theory of the mind has remained elusive.

It is in this context that the Predictive Processing Framework (PPF) has gained significant traction. Proponents claim that its core principle, that the brain is fundamentally a prediction engine striving to minimize error, offers a parsimonious mechanism with the vast explanatory scope needed for unification (Clark 2016; Hohwy 2013). Yet, such a bold claim demands rigorous testing, not just against the standard subjects of perception and action, but against the hard cases: the complex, subtle, and seemingly peripheral phenomena of human cognition.

Prior accounts of humor have offered valuable cognitive frameworks, such as the incongruity-resolution model (Hurley, Dennett & Adams 2011), but often lack a grounding in a more fundamental, domain-general theory of neural processing. This paper will subject the PPF to such a test, using human humor as its litmus. Our task is to determine whether this single, efficient model can explain something as nuanced, subjective, and cognitively strange as a joke, thereby subsuming prior models within a more basic neurocomputational logic.

2. The Predictive Brain: A Parsimonious Engine

The central tenet of PPF is that the brain is not a passive recipient of sensory information, but an active and incessant prediction engine. At every level of its hierarchy, from low-level sensory cortices to high-level conceptual centers, the brain generates models to predict the incoming flow of data. When the prediction aligns with reality, the prediction error signal is suppressed, and conscious experience proceeds smoothly. When reality violates the prediction, the system generates a “prediction error” signal.

According to the framework, the fundamental imperative of the system is to minimize this prediction error over time. It can achieve this in one of two ways:

- Update the Model: The brain can adjust its internal predictive models to better fit the world. This is the basis of perception and learning.

- Change the World: The brain can issue motor commands that alter the world (and thus future sensory input) to make it conform to the prediction. This is the basis of action.

This singular principle of error minimization has been successfully applied to phenomena ranging from the perception of optical illusions to the mechanics of motor control. The question before us, however, is whether it possesses the subtlety to account for humor.

3. Error and Resolution: The Cognitive Mechanics of the Pun

Let us first consider a standard joke structure, the pun: “I just read a book about anti-gravity. It was impossible to put down.” The experience of “getting” this joke maps cleanly onto the PPF model in a three-stage process:

- Prediction: The setup (“a book about anti-gravity”) primes a high-level predictive model expecting a comment on the book’s content or quality (e.g., “…it was fascinating”).

- Error: The punchline (“…impossible to put down”) arrives. The initial, literal interpretation of this phrase generates a significant prediction error, as it conflicts with the established “book review” model.

- Resolution: The brain, seeking to minimize this error, rapidly searches for an alternative model. It quickly finds a better fit: the idiomatic model, where “impossible to put down” is a cliché for a highly engaging book.

Many cognitive theories of humor, such as incongruity-resolution theory, have long identified this basic structure. PPF does not necessarily replace these accounts but provides a neurocomputational foundation for them. The “incongruity” is a high-magnitude prediction error, and the “resolution” is the successful minimization of that error. The pleasure elicited, the “Haha!,” is theorized to be the cognitive reward signal for this rapid and successful error minimization. The pleasure of insight becomes the laughter of recognition: the brain rewarding itself for efficient error reduction

4. The Pleasure of Irresolution: Precision-Weighting and Nonsense

This tidy model of error-and-resolution faces a powerful counter-argument: nonsense. A great deal of humor, from surrealist comedy to internet memes, is funny precisely because it lacks a coherent resolution. Consider the “Why do they call it oven?” copypasta (see Figure 1), a text which begins as if setting up a joke but rapidly devolves into semantic and grammatical chaos. There is no pun to resolve, no clever insight to be had.

Here, PPF’s explanatory power deepens by introducing a crucial, second concept: precision-weighting. Precision is the brain’s estimate of the reliability or importance of a prediction error. A high-precision error is treated as a significant, urgent signal that the brain’s model of the world is dangerously wrong. In a low-stakes context, however, the brain assigns low precision to the error signal. This acts as a “play” signal, flagging the mismatch as safe and inconsequential to the brain’s survival-oriented world model. Nonsense humor, then, can be defined within the PPF as the pleasurable experience of a high-magnitude, low-precision prediction error; in other words, a large mismatch that the system has already tagged as inconsequential. The system registers the catastrophic failure of its models to make sense of the input, but because the error is marked as unimportant, the resolution is simply to abandon the attempt.

5. Cognitive Illusions and Persistent Laughter: The Hierarchy of Prediction

If resolution explains the ‘Aha!’ of the pun and safe irrelevance the ‘Haha!’ of nonsense, a further puzzle remains: why do we continue to laugh even when the trick is known? This framework elegantly explains why a piece of nonsense can remain funny even when one consciously knows it is unresolvable. The experience of re-reading the “Oven” comic and laughing involuntarily, despite high-level knowledge that it is meaningless, exemplifies this. The text functions as a cognitive illusion.

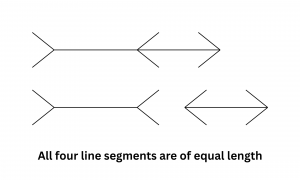

This is analogous to the Müller-Lyer illusion (see Figure 2), where one’s low-level visual system cannot help but see one line as longer than the other, even when one’s high-level knowledge confirms they are identical.

The low-level predictive machinery operates with a degree of automaticity that is insulated from conscious, reflective belief. When re-reading the nonsensical text, the fast, automatic, low-level language-processing systems in the brain cannot stop themselves from attempting to parse grammar and predict meaning. Each time, they boot up, encounter the semantic wreckage, and generate a massive, low-precision error signal. We are, in a sense, laughing from a higher level of our own cognitive hierarchy at the predictable, involuntary failure of a lower one. The joke is no longer just the text itself, but the reliable spectacle of our own mind’s machinery seizing up.

6. Conclusion: The Explanatory Power of a Parsimonious Tool

The Predictive Processing Framework provides a remarkably thorough and continuous explanation for a wide spectrum of humor. It explains the pleasure of simple puns, where an error is efficiently resolved. It accounts for the delight of surreal nonsense, where a large error is safely abandoned. Furthermore, it clarifies the persistence of humor in cognitive illusions, framing it as the meta-pleasure of observing our own automatic error generation. We did not require a separate “pun theory” and a “nonsense theory.” One tool, when applied with nuance, did the work of both.

This is the very picture of theoretical virtue. That a framework a neuroscientist might use to explain motor control can also be used to explain why an internet meme remains funny is a powerful testament to PPF’s explanatory scope. That a framework for neural processing can find its confirmation in the most seemingly frivolous of human experiences, the joy of absurdity, is perhaps the most compelling punchline of all; an elegant confirmation that explanatory power can itself be a kind of beauty.

References

Clark, Andy. 2016. Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hohwy, Jakob. 2013. The Predictive Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hurley, Matthew M., Daniel C. Dennett, and Reginald B. Adams, Jr. 2011. Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.